We’ve all heard the statistics: Today, nearly 55 million people suffer from Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias. According to the WHO, dementia is the fastest growing burden on healthcare systems and the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. Its estimated cost to society is more than US$1.3 trillion every year—and it could be twice that by 2030.

It can be difficult to comprehend the true toll these numbers represent, but it quickly comes into focus for anyone who has ever cared for or watched a loved one suffering from dementia. I lost my dad to Alzheimer’s one year ago, so I understand firsthand the anguish caused by a disease for which there is still no effective treatment.

And yet I have never been more optimistic about the progress being made in Alzheimer’s research, and the breakthroughs that may someday soon let us substantially alter the course of the disease. Finding a cure for Alzheimer’s requires sustained innovation in five critical areas. We need to understand the underlying causes of the disease; improve detection and diagnosis; increase the pipeline of therapeutics; and remove barriers, especially for people from underrepresented populations, to enroll in clinical trials. Finally, to accelerate advances in all these areas, the global community must facilitate more and better access to data.

In the past few years, we have seen tremendous progress on all fronts. But I’m highly encouraged about two areas in particular: diagnostics and data sharing.

Diagnostics

Three and a half years ago, I partnered with the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation and a number of other investors to create the Diagnostics Accelerator. Since its inception, the Diagnostics Accelerator has committed $50 million in more than 35 projects focused on developing reliable, affordable biomarker tests for Alzheimer’s, with promising results. For example, researchers at the University of Gothenburg are working on a method for measuring beta amyloid protein fragments in the blood. The medical imaging company RetiSpec has found a way to use hyperspectral imaging to detect beta amyloid in the retina. Cogstate, Altoida, and others are developing digital tools that can help monitor psychological and behavioral changes associated with neurodegenerative disorders.

I’m particularly excited about the GAP Foundation’s recently announced Bio-Hermes study. It will allow researchers to evaluate new ideas for diagnostics—such as blood and ocular biomarker tests and cell phone apps—by comparing their results with the results of proven approaches, such as brain amyloid PET scans and traditional cognitive tests. This will accelerate the search for new diagnostics.

I’m optimistic that we’ll soon have a number of inexpensive, non-invasive methods for diagnosing Alzheimer’s and other dementias much earlier in their development.

Collaboration and data sharing

It’s encouraging to see the speed and scale of the research that’s currently underway. To accelerate the pace of discovery, however, we must do more to maximize data sharing and collaboration. Sharing data allows researchers to look at the information from many studies at the same time, with the possibility of testing hypotheses or finding patterns and pathways that the original investigator wasn’t looking for.

A few years ago, a coalition of organizations—industry, academia, advocates, and government—came together to address this need. The effort to facilitate more and better access to data culminated in the launch of the Alzheimer’s Disease Data Initiative (ADDI). ADDI’s focus is three-fold: increase the secure sharing of dementia-related

data from academic and industry sources, make it easier to share data across platforms around the world, and empower researchers to find, combine, and analyze data that could lead to new discoveries.

Today, more than 2,000 researchers from 80 countries and regions have embraced the ability to work with multiple datasets in ADDI’s secure environment, and that number is growing every day.

Data sharing also helps bridge the diversity gap that is inherent in most patient datasets. Alzheimer’s is not limited to any one country, culture, or race. Yet, all too often, researchers are working with datasets from predominantly white patient groups, especially in North America, Western Europe, and Australia. If we can increase access to data from studies in Africa, East and South Asia, Latin and South America, or those focusing on a diverse group of participants, we can further our approach to this global disease. In the U.S., the Bio-Hermes study has committed to ensuring that 20% of its study participants are African American or Hispanic, setting the standard for future research and development.

The path forward

All of us can play a part in these efforts. If you’re a researcher, thank you—I hope you’ll continue your work on new diagnostics, treatments, and cures. If you are living with Alzheimer’s or have a loved one who is, I hope you’ll consider participating in a trial or study. As new diagnostics come along, it will be easier to know whether you’re a good match for a trial. Finally, governments, industry groups, and foundations should keep funding research and development, and invest even more.

I believe that humans are capable of solving almost any problem through innovation—and I see countless opportunities for innovation in this field. I’m optimistic that if we all work together, we can defeat dementia.

__________

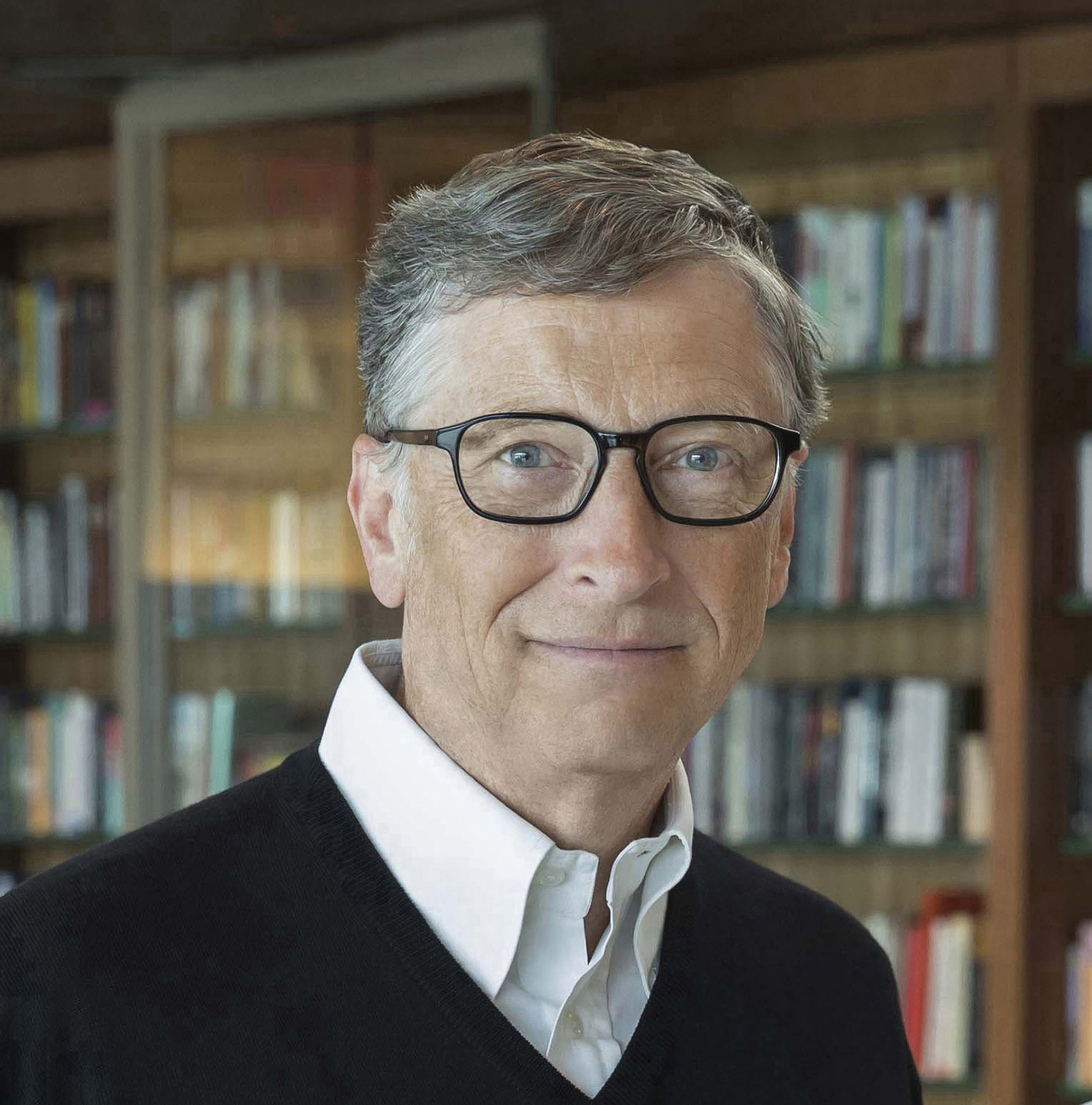

Bill Gates is co-founder of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation